How to Get Meaningful Feedback on Your Design Document

You’ve spent weeks carefully writing a design document for your software project, but what happens next? How can you get useful feedback about it from your teammates? How do you prevent your design review from dragging on for months?

I’ve been through many design reviews in my career as both the author and reviewer, and I have a special fondness for effective reviews. Through trial and error, I’ve learned techniques that help the review process move smoothly and yield material improvements to the design.

- Goals of an effective design review process

- Write an introduction that makes sense to everyone

- Make it easy for reviewers to give you feedback

- Invest effort in clear diagrams

- Give reviewers time to read independently

- Start with a single reviewer

- Address feedback in the doc itself

- Aggressively resolve comment threads

- Resolve contentious issues in a focused meeting

- Conduct a design postmortem

- Summary

Goals of an effective design review process🔗

Identify design flaws🔗

The most valuable outcome of a design review is to find design flaws or opportunities to simplify your system. Some design decisions are incredibly costly to change later, so it’s best to catch these mistakes as early as possible.

For example, if you plan to store data in Google Cloud Firestore, a teammate might point out that SQLite satisfies your requirements with less complexity. That single piece of feedback can save you hundreds of hours over the project’s lifetime (ask me how I know).

Get everyone on the same page🔗

The system you’re designing doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Your project impacts other people on your team and in your company. A design review coordinates plans with your partners early in the process, when misalignments are easiest to fix.

Keep moving forward🔗

One of the worst pitfalls of a design review is stalling out. When a review devolves into dozens of mini-fights, you get stuck arguing rather than improving your design. An effective design review keeps everyone moving forward rather than letting conflict consume the process.

Maximize value of your teammates’ focus🔗

Your teammates arrive at work each day with eight hours to allocate, but they can only spend a precious fraction of that time on deep, focused thought. Reviewing a design doc requires intense focus. Don’t squander it by forcing your reviewers to look up jargon terms they don’t recognize or to piece together context you should have provided.

Strengthen design skills across the team🔗

Many engineers struggle to improve their high-level design skills because they don’t get many opportunities to practice. Their day-to-day work is mainly chasing bugs and making incremental changes to the codebase.

Reviewing a design doc exercises the same muscles as writing one. It also gives teammates perspective about what makes a design doc easier or harder to review.

AI-assisted programming isn’t going away anytime soon, but senior-level design continues to elude even the best AI assistants. In a world where LLMs take over more programming tasks, the most valuable developers will be the ones who can think about architecture from multiple abstraction layers, weigh competing engineering tradeoffs, and specify behavior clearly.

Write an introduction that makes sense to everyone🔗

Early in my career, I signed up for a mentorship program that matched me with a senior engineer at my company. He asked me to come to our first meeting with a design doc I’d written. As I handed it to him, I explained the background of the project and how it aligned with my team’s goals. He frowned.

“Everything you just told me should be on the first page of your design doc,” he said, bluntly.

He was right.

I wrote the design doc imagining how my teammates would read it, but I failed to consider other readers. There was a broader audience beyond my immediate team, including partner teams, mentors, and promotion committees. They should all have been able to understand it as well.

When journalists write newspaper articles, they write in a style called “the inverted pyramid.” A good news report begins with the details that interest a broad audience, then progressively narrows its focus to details that interest only the most engaged readers.

Journalists structure news reports in an inverted pyramid, where the information relevant to the most people is at the top.

The early sections of your design doc should make sense to anyone you expect to read your design, whether they’re an expert in the codebase or a member of a partner team who’s never seen a line of code in their life.

Start the design doc with your goals and the concrete scenarios your design doc addresses. Replace jargon terms with words that make sense to any potential reader.

Arrange your design doc so that the early sections makes sense to everyone you expect to read it. As you get further into the document, assume the audience is smaller and smaller as people stop reading things that are irrelevant to them.

As you get deeper into your document, you can assume the reader has more context, but keep your target audience in mind for each section. If you’re designing a REST API for a partner team, they care about the API semantics and your reliability targets, but they probably won’t read the sections about how you’ll log diagnostic messages or store persistent data.

Make it easy for reviewers to give you feedback🔗

My first software job was at Microsoft in the late 2000s. They weren’t sure about the whole “cloud” thing yet, so we gathered design feedback by emailing around dozens of variants of the same Word document with different reviewers’ notes. If the document contained a broken link or an undefined term, the only way to fix it was by saving it as a new file and emailing it to everyone again.

Fortunately, in 2025, we have better tools for reviewing design docs. The most important features to look for are (from most important to least important):

- Reviewers can write comments to you as they read the document.

- The document has a single URL that remains consistent throughout the review process.

- Reviewers can see the changes you’ve made to the document since their last review.

Google Docs and Office 365 Word are both popular, user-friendly options that comfortably achieve #1 and #2. They do #3 poorly, but well enough to get by.

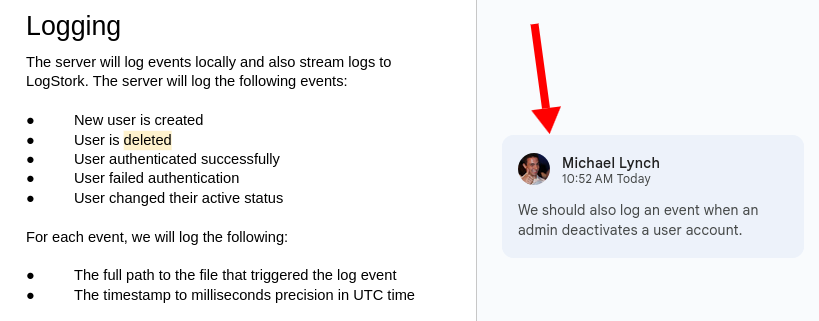

Google Docs makes it easy for reviewers to leave comments in the margins of your design doc.

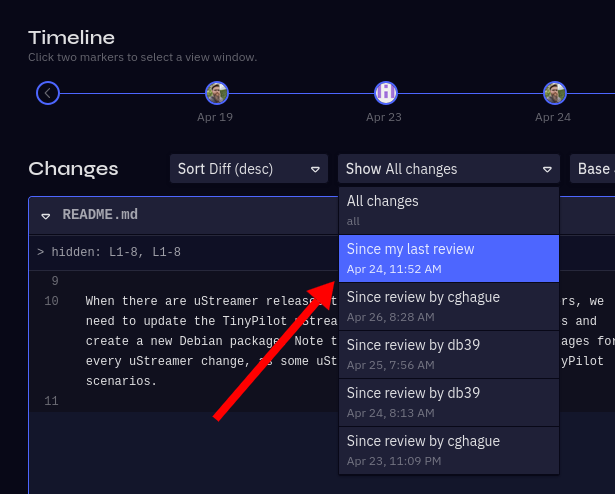

When my audience is exclusively developers, I prefer writing in Markdown and reviewing with my team’s standard code review tools. All code review tools support #1 and #2. GitHub pull requests handle #3 poorly, but CodeApprove, Gerrit, and Reviewable all support it well.

CodeApprove makes it easy for reviewers to see all the changes to a file since their last review.

Invest effort in clear diagrams🔗

Whenever I send a design doc out for review, about 50% of the feedback is about my diagrams. That’s a good thing.

My reviewers aren’t nitpicking my diagram’s color scheme or choice of shapes; they’re talking about my diagrams because they facilitate intelligent, constructive discussions about my architecture and design decisions. Don’t skimp on your diagrams.

If you’re not sure what belongs in a diagram, think about these questions:

- How do the different components of your system fit together?

- How does data flow through your system?

- How does your system interact with its dependencies and downstream clients?

- What are the distinct steps of a complex process or protocol?

Choose a diagramming tool that’s flexible to editing. I’ve seen people draw beautiful whiteboard diagrams with colored markers, and then photograph it for their design doc. Their first draft looks amazing, but then they can never change it.

Excalidraw, Google Drawings, and Mermaid are all popular diagramming tools that facilitate iterative revisions. Link back to the source drawing to let your teammates adapt it in the future, if they need to.

Give reviewers time to read independently🔗

I’ve been in “design review” meetings where the author hands out a doc nobody has seen before and hastily reads excerpts while everyone else patiently listens.

That’s not a design review.

If you ambush your reviewers with a design doc and talk nonstop while they try to read it, they’re not going to be able to think critically and give you constructive feedback. Give your reviewers time to review your doc at their own pace when they have focus.

I give reviewers a minimum of two working days to review a design doc. I add more time depending on the complexity of the project and the number of other concurrent high-priority tasks.

Start with a single reviewer🔗

When you finish the first draft of your design doc, you just want to get your doc approved as quickly as possible so you can start coding.

Resist the temptation to blast your doc out to everyone at once. Instead, start with a preliminary review from a single reviewer.

Your first draft almost certainly contains mistakes and logical gaps. If a reviewer has trouble understanding your design because your wording is unclear or you forgot to explain something, it’s better to fix that with a single reviewer than to let 10 people trip over the same mistake.

The other reason to get a preliminary review is to avoid the bystander effect. When you send your design doc to 10 people, they might all assume they can give it a quick skim because somebody else will review it carefully. If you ask a specific person, they know you expect a thorough review.

I usually ask for a preliminary review from the person who has the most invested in my project. This can be someone who plans to implement the project with me, a potential client of the project, or the owner of an upstream dependency.

The preliminary review isn’t to polish your doc to perfection. Just aim for a doc that makes sense. Focus on fixing your explanation rather than the design itself.

If your reviewer has suggestions for uncontroversial design improvements, go ahead and integrate them before sharing the doc with other teammates. Otherwise, leave the reviewer’s design critiques as open issues to resolve during the wider team review.

Address feedback in the doc itself🔗

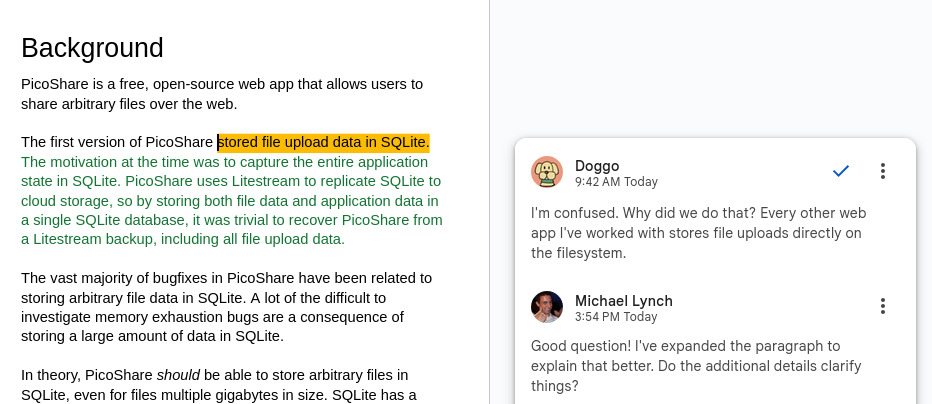

When someone asks you a question about your doc or misunderstands something, resolve their confusion in the doc itself. Don’t explain things “out of band” in comment threads, chat conversations, emails, or in-person conversations. Otherwise you haven’t fixed anything; everyone else who reads the doc will have the same issue.

When reviewers ask questions about your doc, answer them by improving your doc so other readers don’t have the same question.

If you really can’t answer the question in the doc, talk it through with your reviewer, but always circle back to update your doc with whatever insight finally made the concept click. Ask you reviewer to confirm that the new wording reflects your out-of-band discussion.

Aggressively resolve comment threads🔗

When I worked at Google, any time I tried to read a historical design doc, it was nearly impossible. Every page was covered in margin notes that contradicted the design. It was never clear whether the dev team implemented the original design or an idea from the margin discussion.

Every historical design doc I read at Google had dozens of margin threads with hundreds of comments, and it was never obvious which were still relevant.

As the design doc author, you’re responsible for driving comment threads to resolution as quickly as possible. Do not leave dangling threads.

Respond to margin notes and mark the thread resolved if you’re confident you addressed the note. If you’re unsure, ask the reviewer. If they don’t respond after a few days, mark the thread as resolved.

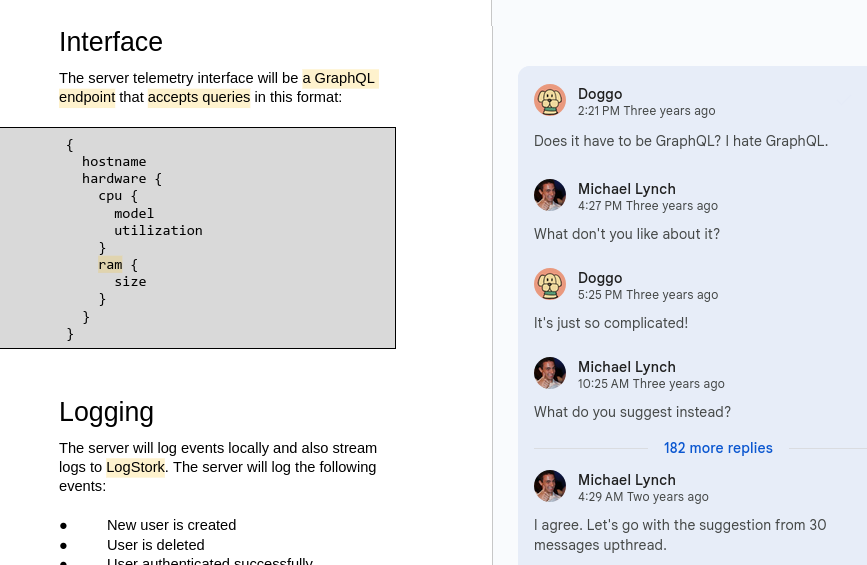

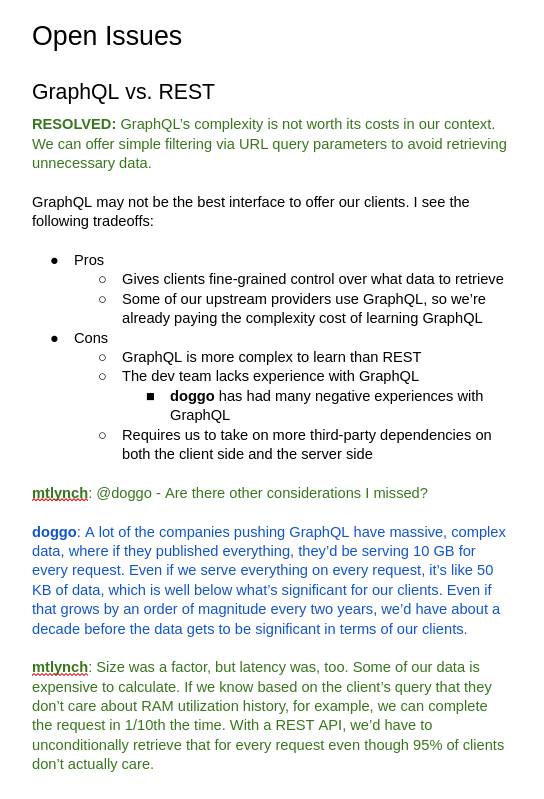

If discussion remains open after two or three back-and-forths in the margin notes, move the discussion to an “Open Issues” section in the appendix. Explain the open issue by describing the different perspectives from the margin discussion as fairly as you can. Invite reviewers to leave additional feedback prefixed with their username or initials.

If margin discussions grow beyond two or three back-and-forths, add a dedicated section in the appendix to discuss the issue with your team. This gives you more room to discuss and eliminates noise in the main body of your doc.

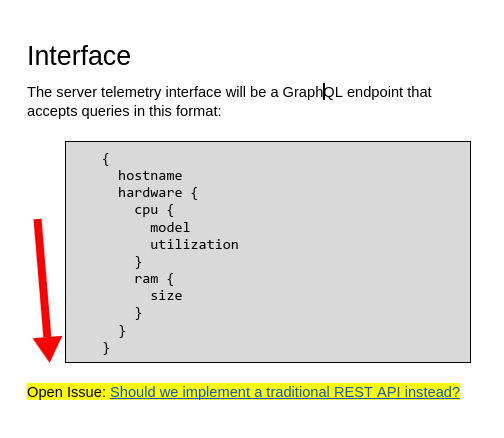

Once you’ve summarized a comment thread with an open issue in the appendix, resolve the original thread and place a link to the open issue in the section where the discussion occurred.

When you move a discussion to an open issue appendix, include a link in the section of your doc that prompted the discussion.

If you resolve the open issue in a few more back-and-forths in the appendix, great! Summarize the rationale at the top, and update your doc to reflect the final decision.

When you resolve an open issue, summarize the decision at the top of the section.

If you’re unable to resolve the open issue quickly, reserve it for a live discussion (see below).

Resolve contentious issues in a focused meeting🔗

Many teams mistakenly schedule a meeting as the first step of a design review, but it should actually be the last step.

You should hold a meeting to resolve any outstanding issues that remain after everyone has had a chance to review the design document, propose alternative options, and understand the pros and cons of each proposal.

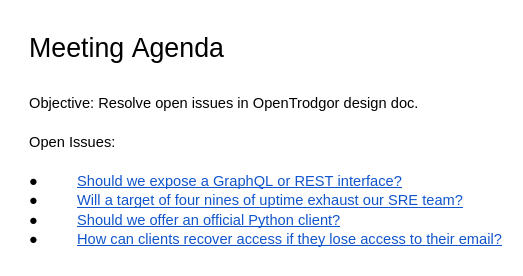

The point of this meeting is to resolve any remaining open issues and drive your design to approval. When you schedule the meeting, share a written agenda ahead of time that outlines the issues you’re trying to resolve. Make sure attendees understand that the meeting is not an invitation to make last-minute objections to previously uncontroversial design decisions.

Share a written agenda ahead of the meeting that focuses the meeting specifically on outstanding open issues. Otherwise, attendees may think you’re inviting them to comment on any part of the design.

Conduct a design postmortem🔗

Postmortems are typically for disasters, but they’re also useful for proactively improving processes even in the absence of catastrophe.

After you code a working implementation based on your design doc, conduct a blameless postmortem of the design process. By blameless, I mean that you focus on process rather than individual mistakes.

For example, if your launch date slipped by two weeks because Michael forgot to request servers ahead of time, the postmortem shouldn’t ask, “Why is Michael so forgetful?” but rather, “How can we adjust our process to avoid depending on human memory?”

Here are some good questions to ask when gathering feedback for a postmortem:

- Which tasks took longer than expected?

- Which dependencies did not work as expected?

- Which details were overlooked at design time?

- What process changes would reduce your risk of similar oversights in the future?

- Which tasks went smoothly?

- What aspects of the design process contributed to their success?

I generally approach a design postmortem like this:

- Create a list of things you think went well or poorly.

- (Optional) If your team doesn’t have experience with blameless postmortems, explain that it’s an exercise to improve processes and not to point fingers.

- Google’s SRE book includes a good introduction to blameless postmortems.

- Email a questionnaire (like Tally or Google Forms) to teammates who participated in the design process.

- Discourage any reply-all answers, as they bias subsequent responses and encourage groupthink.

- Answer your own questionnaire first to avoid bias from your teammates’ answers.

- Aggregate everyone’s responses into a postmortem document.

- Order the issues so that the most common responses and most severe issues appear first.

- Send the postmortem document to your teammates.

- Schedule a meeting to review the postmortem document.

- In the meeting, go through each item in the postmortem and brainstorm ways to improve the design process in the future.

Here’s an example of what an entry might look like in a design postmortem:

Issue: The DuckDB integration took six weeks, nearly 2x the initial estimate🔗

Contributing factors

- We didn’t realize at design time that there were no Objective-C bindings available for DuckDB, so we had to write a lot of custom glue code on top of the Swift API.

- Nobody on the team had experience with DuckDB. We estimated based on previous SQLite integrations, which turned out to not be predictive of our DuckDB work.

- We encountered more DuckDB bugs and gotchas than we expected.

Takeaways

- Consider language bindings when selecting a database technology.

- Weigh team inexperience with a technology more heavily in estimating timelines.

- Weigh the maturity of the technology more heavily in estimating timelines.

Summary🔗

- An effective design review capitalizes on the work you invested in your design document and expands its benefits.

- Structure your design document so that early sections are intelligible to any reader you expect to see your doc.

- Use tools like Google Docs or Office 365 to make it easy for reviewers to leave you comments as they read your doc.

- Work hard to create clear diagrams, as they’re the most effective way to communicate your design to reviewers.

- Give your reviewers time to read your design doc asynchronously so they can review it with their full attention.

- Work through major issues with a single reviewer before sharing the doc with the full team.

- Treat every question or misunderstanding as an opportunity to improve your design doc and eliminate the confusion for future readers.

- Quickly resolve comment threads, and integrate the outcome of the discussion into the doc itself.

- Use a dedicated meeting to resolve any contentious issues you can’t resolve through text-based discussion.

- After you implement your design, look for opportunities to improve your design process based on the project’s outcome.

“Gateway Sink” illustration by Piotr Letachowicz.